News and Blogs

A Comprehensive Guide to Specimen Collection for Gastrointestinal Pathogen Detection

Gastrointestinal (GI) pathogens are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, leading to a range of symptoms and conditions such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and dehydration. The accurate detection of these pathogens is crucial for prompt diagnosis, effective treatment, and successful management of patients suffering from gastrointestinal infections. Specimen collection plays a pivotal role in the process of detecting and identifying these pathogens. The quality and integrity of the collected specimens directly impact the accuracy and reliability of the laboratory tests used for pathogen detection.

This comprehensive guide aims to provide a thorough understanding of the various aspects of specimen collection for gastrointestinal pathogen detection, highlighting the importance of proper techniques and procedures. The guide covers different types of gastrointestinal pathogens, the various specimens used for their detection, and the most effective collection techniques for each type of specimen. Furthermore, it discusses the handling, storage, and transport of specimens, laboratory testing methods, interpretation of results, and infection control measures.

By following the principles and techniques outlined in this guide, healthcare professionals can ensure that specimens are collected accurately and efficiently, ultimately leading to more accurate diagnoses and better patient outcomes. The guide also serves as a valuable resource for researchers and laboratory personnel involved in the detection and study of gastrointestinal pathogens.

I. Types of gastrointestinal pathogens

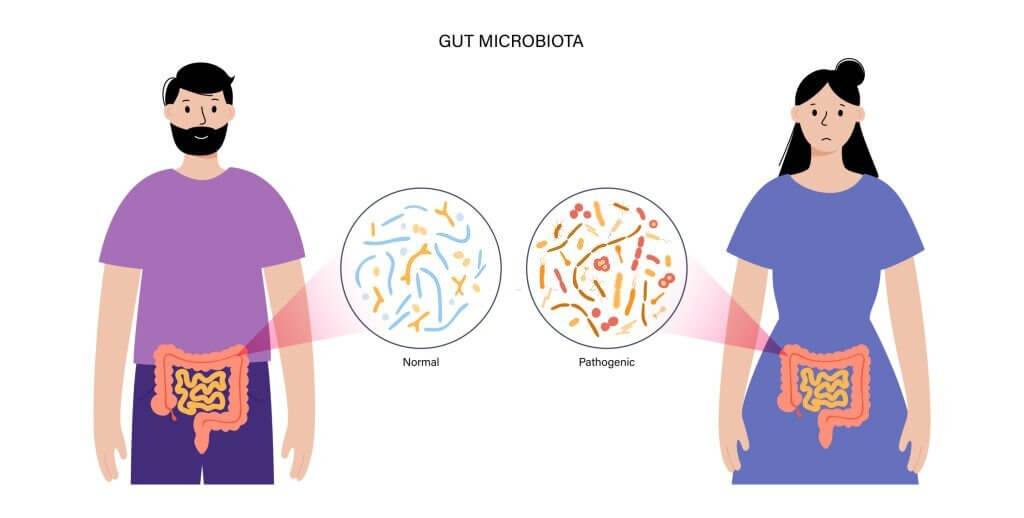

Gastrointestinal infections can be caused by a wide range of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi. Each type of pathogen has its unique characteristics, modes of transmission, and clinical manifestations. In this section, we will provide an overview of the most common types of gastrointestinal pathogens, which will help healthcare professionals better understand the context of specimen collection and detection.

A. Bacteria

Bacterial gastrointestinal infections are common and can be caused by various bacterial species. Some of the most frequently encountered bacterial pathogens include Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, and Clostridium difficile. These bacteria can cause infections ranging from mild gastroenteritis to severe, life-threatening conditions such as toxic megacolon or sepsis. Bacterial infections are typically acquired through ingestion of contaminated food or water, person-to-person contact, or contact with contaminated surfaces.

B. Viruses

Viral gastrointestinal infections, commonly referred to as viral gastroenteritis, are usually self-limiting and generally less severe than bacterial infections. The most common viral pathogens responsible for gastroenteritis include norovirus, rotavirus, adenovirus, and astrovirus. These viruses are highly contagious and can spread rapidly through contaminated food, water, or contact with infected individuals. Outbreaks often occur in closed settings such as schools, hospitals, and cruise ships.

C. Parasites

Parasitic gastrointestinal infections can be caused by various protozoan and helminth species. The most common protozoan parasites include Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium, and Entamoeba histolytica, which typically cause diarrheal illness, abdominal pain, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Helminths, or parasitic worms, such as Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, and hookworms, can also infect the gastrointestinal tract, causing malnutrition, anemia, and other complications. Parasitic infections are often acquired through ingestion of contaminated food or water, contact with infected individuals, or exposure to contaminated soil.

D. Fungi

Fungal gastrointestinal infections are less common than bacterial, viral, or parasitic infections but can still cause significant morbidity in certain populations, particularly immunocompromised individuals. Candida species are the most common cause of fungal gastrointestinal infections, typically manifesting as oral thrush or esophagitis. Other fungi, such as Aspergillus or Cryptococcus, can also cause gastrointestinal infections in rare cases. Fungal infections are usually acquired through ingestion of contaminated food or inhalation of fungal spores.

II. Specimen types for gastrointestinal pathogen detection

The accurate detection of gastrointestinal pathogens relies on the appropriate choice and collection of specimens. Several types of specimens can be used for detecting these pathogens, each with its specific advantages and limitations. In this section, we will discuss the most commonly used specimen types for the detection of gastrointestinal pathogens.

A. Stool samples

Stool samples are the most frequently collected specimens for gastrointestinal pathogen detection, as they contain high concentrations of the causative organisms. They are particularly useful for the diagnosis of bacterial, parasitic, and viral infections. Depending on the suspected pathogen, different parts of the stool sample may need to be analyzed. For example, bacterial pathogens are usually found in the outer layer of the stool, while parasites are more commonly found in the central portion.

B. Rectal swabs

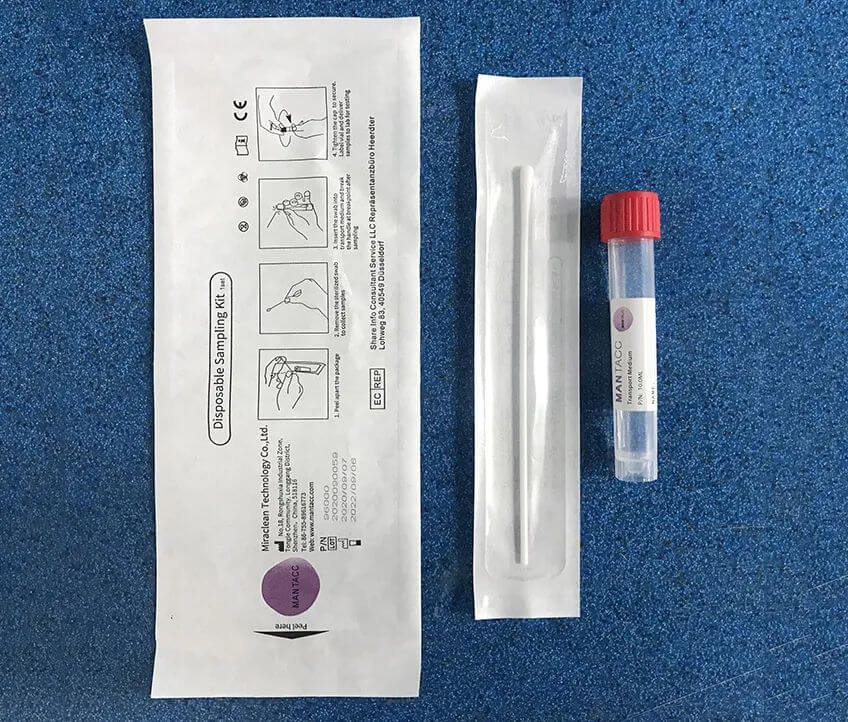

Rectal swabs are an alternative to stool samples for the detection of gastrointestinal pathogens, particularly when obtaining a stool sample is not possible or practical. They are less invasive than some other collection methods and can be easily collected from patients, including children and infants. Rectal swabs are most suitable for the detection of bacterial and viral pathogens but may not be as effective for detecting parasites, which are usually present in lower numbers in rectal samples.

C. Duodenal aspirates

Duodenal aspirates involve the collection of fluid from the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine, using an endoscope. This type of specimen is particularly useful for the diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and for detecting parasites such as Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium. The procedure requires specialized training and equipment and is more invasive than stool samples or rectal swabs.

D. Tissue biopsies

Tissue biopsies involve the removal of a small sample of tissue from the gastrointestinal tract, typically during an endoscopic or surgical procedure. Biopsies are particularly useful for detecting pathogens that cause localized infections, such as Helicobacter pylori (which causes gastric ulcers) or invasive fungal infections. Tissue biopsies can also be used to assess the extent of tissue damage and inflammation caused by the infection, providing valuable information for patient management.

III. Collection procedures and techniques

Proper collection procedures and techniques are critical for obtaining accurate and reliable results in the detection of gastrointestinal pathogens. In this section, we will discuss the specific collection procedures for each specimen type, as well as pre-collection preparation steps.

A. Pre-collection preparation

- Patient instructions: Before collecting any specimen, it is essential to provide clear instructions to the patient. These instructions should include information on the collection process, the use of collection devices, and any dietary or medication restrictions that may affect the test results.

- Collection kit and supplies: Ensure that all necessary collection supplies, such as sterile containers, swabs, and gloves, are available and appropriately labeled before starting the collection process. Using the correct supplies ensures the integrity of the sample and minimizes the risk of contamination.

B. Stool sample collection

- Timing and frequency: Depending on the suspected pathogen, multiple stool samples may be required to increase the likelihood of detection. Samples should be collected at different times and on separate days, ideally within a 72-hour period.

- Collection methods: Patients should be instructed to collect a small portion of the stool sample, ideally the size of a walnut, using a clean, disposable spoon or spatula. The sample should be placed in a sterile, leak-proof container with a tight-fitting lid. If the sample is to be tested for parasites, a preservative or fixative may be required.

C. Rectal swab collection

- Technique and handling: The healthcare professional should wear gloves and insert a sterile swab approximately 2-3 cm into the patient's rectum, gently rotating it to ensure adequate contact with the rectal mucosa. The swab should then be carefully withdrawn, avoiding contact with the perianal skin, and placed in a sterile transport medium.

- Proper swab type selection: It is essential to use the appropriate type of swab for the suspected pathogen. Some swabs are specifically designed for bacterial or viral pathogens, while others are suitable for a broader range of organisms. Discover our 93050P Anal Sampling Kit: a comfortable, efficient solution with a flocked swab, leak-proof tube, and preservation solution. Quality assured.

D. Duodenal aspirate collection

- Indications and contraindications: Duodenal aspirates should only be performed when there is a strong clinical suspicion of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or parasitic infection, and other less invasive tests have been inconclusive. The procedure should not be performed in patients with certain medical conditions, such as coagulopathy or recent gastrointestinal surgery.

- Endoscopic procedure: The healthcare professional will insert an endoscope through the patient's mouth and advance it to the duodenum. A catheter is then inserted through the endoscope, and a small amount of fluid is aspirated from the duodenum. The sample should be placed in a sterile container and transported to the laboratory as soon as possible.

E. Tissue biopsy collection

- Indications and contraindications: Tissue biopsies are typically performed when there is a suspicion of localized gastrointestinal infections or inflammatory conditions. The procedure should not be performed in patients with certain medical conditions, such as coagulopathy or recent gastrointestinal surgery.

- Endoscopic or surgical procedure: Tissue biopsies can be obtained during an endoscopic procedure, such as gastroscopy or colonoscopy, or during surgery. The healthcare professional will use specialized instruments to remove a small sample of tissue from the affected area. The sample should be placed in a sterile container with appropriate transport medium and sent to the laboratory as soon as possible.

IV. Specimen handling, storage, and transport

Proper handling, storage, and transport of specimens are crucial to maintain their integrity and ensure the accuracy of the test results. In this section, we will discuss the guidelines for handling, storage, and transport of the various specimen types used for gastrointestinal pathogen detection.

A. Handling guidelines

- Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, masks, and eye protection while handling specimens to minimize the risk of exposure to infectious agents and prevent contamination.

- Minimize the time between specimen collection and processing or transport to the laboratory. This helps to maintain the viability of the pathogens and reduce the risk of overgrowth by competing organisms.

- Ensure that all containers and transport media are securely closed and labeled with the patient's information, collection date, and type of specimen.

B. Temperature and storage conditions

- Stool samples and rectal swabs: Most bacterial and viral pathogens can be stored at 2-8°C for up to 48 hours. However, certain pathogens, such as Campylobacter, may require storage at lower temperatures (e.g., -20°C) or in specialized transport media. Parasite samples should be stored in a preservative or fixative solution at room temperature.

- Duodenal aspirates: Store duodenal aspirates at 2-8°C and transport them to the laboratory within 2 hours of collection, as bacterial overgrowth can occur rapidly at room temperature.

- Tissue biopsies: Biopsy specimens should be stored in appropriate transport media, such as formalin or other fixatives, at room temperature. Do not refrigerate or freeze tissue samples, as this may compromise the quality of the specimen.

C. Transport to the laboratory

- Transport specimens to the laboratory as soon as possible after collection, ideally within 24 hours. Delays in transport can result in the loss of viability of the pathogens and degradation of the sample.

- Use appropriate transport containers and packaging materials that comply with local and international regulations for the transport of biological specimens. Ensure that the packaging is leak-proof and properly labeled with the necessary patient and specimen information.

- Maintain the appropriate storage temperature during transport. Use insulated containers or coolers with ice packs or refrigerant gel packs for specimens that require refrigeration.

V. Laboratory testing methods for gastrointestinal pathogen detection

Various laboratory testing methods are available for the detection of gastrointestinal pathogens. Each method has its advantages, limitations, and specific applications. In this section, we will discuss the most commonly used laboratory testing methods for gastrointestinal pathogen detection.

A. Microscopy

Microscopy involves the examination of stool or other specimens under a microscope to identify the presence of pathogens, such as bacteria, parasites, or fungal elements. This technique is particularly useful for the detection of parasites, including protozoa and helminths. However, microscopy is labor-intensive and requires a skilled technician for accurate identification.

B. Culture-based techniques

Culture-based techniques involve the growth of bacteria or fungi from the specimen on specialized culture media. This method is particularly useful for the identification of bacterial pathogens and allows for further testing, such as antimicrobial susceptibility testing. However, culture-based techniques are generally not suitable for the detection of viruses or some fastidious organisms.

C. Molecular diagnostics (e.g., PCR)

Molecular diagnostics, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), involve the amplification and detection of specific nucleic acid sequences of the pathogens. PCR-based techniques are highly sensitive and specific, allowing for the rapid and accurate detection of a wide range of gastrointestinal pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites. However, molecular diagnostics may be more expensive and require specialized equipment and trained personnel.

D. Antigen detection assays

Antigen detection assays involve the detection of specific antigens (proteins or other molecules) produced by the pathogens. These assays are typically performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or immunochromatographic techniques. Antigen detection assays can be rapid and relatively simple to perform, but their sensitivity and specificity may vary depending on the pathogen and the specific antigen targeted.

E. Serological tests

Serological tests detect the presence of antibodies produced by the host in response to infection with a specific pathogen. These tests are particularly useful for the diagnosis of certain viral or parasitic infections, such as hepatitis A or toxoplasmosis. However, serological tests are generally not useful for the diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal infections, as they may not detect the presence of antibodies during the early stages of the infection.

VI. Interpretation of laboratory results

Interpreting laboratory results for gastrointestinal pathogen detection requires a thorough understanding of the testing methods used, the clinical context, and the limitations of each test. In this section, we will discuss the factors to consider when interpreting laboratory results and the importance of clinical correlation.

A. Sensitivity and specificity of testing methods

Each laboratory testing method has its inherent sensitivity and specificity, which can influence the interpretation of the results. A highly sensitive test is more likely to detect true positive cases, while a highly specific test is more likely to correctly identify true negative cases. It is essential to consider the sensitivity and specificity of the testing method when interpreting the results, as false positives and false negatives can occur.

B. Prevalence of pathogens

The prevalence of specific gastrointestinal pathogens in a given population or geographical region can also influence the interpretation of laboratory results. In areas where a particular pathogen is highly prevalent, a positive test result is more likely to be a true positive. Conversely, in areas where a pathogen is rare, a positive test result may be more likely to be a false positive.

C. Clinical context and patient history

Laboratory results should always be interpreted in the context of the patient's clinical presentation, history, and risk factors. A positive laboratory result does not necessarily indicate an active infection, as some tests may detect non-viable organisms or remnants of a previous infection. Similarly, a negative result does not always rule out infection, especially in cases where the test has limited sensitivity or if the specimen was not collected or handled properly.

D. Confirmatory testing

In some cases, confirmatory testing may be necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis. This may involve repeating the initial test, using an alternative testing method, or testing additional specimens. Confirmatory testing is particularly important when the initial test results are discordant with the patient's clinical presentation or when the test has limited sensitivity or specificity.

E. Communication with the laboratory

Close communication between the healthcare provider and the laboratory is crucial for accurate interpretation of laboratory results. Healthcare providers should provide relevant clinical information, such as patient history, travel history, and exposure risks, to help guide the laboratory's testing approach. In turn, the laboratory should communicate any concerns or limitations related to the testing methods or the quality of the specimens received.

VII. Prevention and infection control measures

Infection control measures play a crucial role in preventing the spread of gastrointestinal pathogens within healthcare settings and the community. By implementing appropriate infection control practices, healthcare professionals can minimize the risk of transmission and protect vulnerable populations. In this section, we will discuss the key infection control measures for gastrointestinal pathogens.

A. Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene is the most critical infection control measure for preventing the spread of gastrointestinal pathogens. Healthcare professionals should adhere to proper hand hygiene practices, including washing hands with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers before and after patient contact, after handling specimens, and after using the restroom.

B. Personal protective equipment (PPE)

Healthcare professionals should wear appropriate PPE, such as gloves, masks, and eye protection, when collecting specimens or handling contaminated materials. PPE should be removed and disposed of appropriately to minimize the risk of transmission.

C. Environmental cleaning and disinfection

Regular cleaning and disinfection of surfaces and equipment in healthcare settings are essential for reducing the risk of transmission of gastrointestinal pathogens. Special attention should be given to high-touch surfaces and areas where gastrointestinal specimens are collected, processed, or stored.

D. Isolation precautions

Patients with suspected or confirmed gastrointestinal infections should be placed under appropriate isolation precautions to minimize the risk of transmission to other patients and healthcare personnel. Isolation precautions may include contact precautions, private rooms, or cohorting of patients with similar infections.

E. Education and training

Healthcare professionals should receive ongoing education and training on infection control measures, including hand hygiene, PPE use, and specimen handling. Regular training helps ensure that staff members are knowledgeable about current best practices and are adhering to the recommended guidelines.

F. Surveillance and outbreak management

Healthcare facilities should have a surveillance system in place to monitor the incidence of gastrointestinal infections and identify potential outbreaks. Early detection and prompt intervention are crucial for controlling outbreaks and preventing further transmission. Outbreak management may involve enhanced infection control measures, targeted testing, and communication with public health authorities.

VIII. Conclusion

The detection and management of gastrointestinal pathogens require a multifaceted approach that includes appropriate specimen collection, handling, and transport, as well as the utilization of various laboratory testing methods. A thorough understanding of the advantages and limitations of each testing method, coupled with a careful interpretation of laboratory results, is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, implementing infection control measures, promoting preventive strategies, and engaging in public health interventions and community education are vital to reducing the burden of gastrointestinal infections on both individual patients and the broader community. By following best practices and collaborating with laboratory and public health professionals, healthcare providers can contribute to the ongoing effort to control and prevent gastrointestinal infections, ultimately improving the overall health and well-being of the population.

Want to learn more about our fecal swabs?

Mantacc presents an extensive selection of premium flocked swabs designed for various sampling purposes, including nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, cervical, rectal, and object surface collection, ensuring optimal comfort for patients. If you require specific materials or sizes not found in our existing range, our expert customization service is available to accommodate your needs. To explore our swab offerings, please click here or click on the image below to connect with our sales representatives.

Find Products: Fecal Swabs

Everything You Need To Know About Cervical Specimen Collection

Specimen Collection and the Ongoing Battle Against Tuberculosis in Indigenous Populations

The Science of Detection in Forensic Drug Testing and Specimen Collection Methods

A Comprehensive Guide to Specimen Collection for Gastrointestinal Pathogen Detection

Nasopharyngeal Swab vs Oropharyngeal Swab: Which is Better In Specimen Collection?

What is An Effective Specimen Collection and Transport System?

Related Posts